Carl Eduard Hartknoch

(Riga 1796 – Moscow 1834)

The compositions mentioned below are in a 63 pages volume

Sonate

Allegro con brio

Sonate

Adagio con gran espressione

Sonate

Allegretto grazioso

Grand rondeau russe

Adagio molto

Allegro

Trois nocturnes caractéristiques

Andante

Trois nocturnes caractéristiques

Andantino con espressione

Trois nocturnes caractéristiques

Andante

Carl Eduard Hartknoch

Progressive pianistic ideas and old-fashioned polyphony

Bart van Sambeek

In 1997 I was given a convolute to peruse in the library of the Brussels conservatory. While browsing through a composition by Kalkbrenner, Hartknoch’s opus 1 suddenly appeared. Hartknoch was born in Riga in 1796. Despite a university education (which one is unclear), he made his debut in Leipzig in 1816 as a concert pianist and decided to continue in music. In 1819 he went to Weimar to study with Hummel, but left for Petersburg in 1825 because apparently no work could be found in his immediate vicinity. In Russia he was a highly respected piano teacher. In 1828 he moved to Moscow where he died in 1834.

It is not easy to determine how many opus numbers he wrote in total. Much further than an incomplete list that runs up to and including opus 14 is not possible at the moment.

It is clear that the composer wanted to make an impression with his first published work: a full and varied score image on 25 pages of old print. Once behind the piano with this piece on the music stand, I could not keep my hands off it for weeks.

Hartknoch is mentioned several times in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung (AMZ) between 1821 and 1825. This Leipzig journal published reviews of new editions and discussions on all kinds of musical subjects for decades (between 1799 and 1848). It is still a very readable source and the reviewers from that journal judge the concerts and compositions they attend with a very critical ear. Hartknoch often plays pieces by Hummel in public and the AMZ is very positive about it: …und [zeugt] sein Spiel von vieler mechanischen Fertigkeit und tiefem Gefühl. And a little further on: …und dabey abermals grosse Fertigkeit und Präcision bewährt.

In February 1822, his first opus number (a piano sonata) was reviewed with great praise in AMZ. It starts like this: Diese Sonate verdient von zweyen Seiten eine mehr als gewöhnliche Aufmerksamkeit bedeutender Klavierspieler, und wahrhaft gebildeter Musikfreunde überhaupt: um ihres Gehalts und Werthes, und um Verfassers wille. And further on: …aber der harmonische [Antheil] ist noch reicher und ausgezeichneter. Die Schreibart ist durchgehends vollstimmig…d.h. in allen Stimmen geordnet, …nicht selten auch melodisch fortgeführt. Hartknoch has a preference for polyphony and his themes would not be out of place in a fugue. Below (after a few introductory bars), the first theme of the first movement. It is a striking melody that starts with an octave jump and a falling fifth:

The second theme is more lyrical and the head of the first theme is somewhat hidden in the left hand:

And a little later:

The reviewer notes that teacher Hummel sounds a little too much in the first part. However, he is very pleased with parts 2 and 3: …aber im Adagio und im Finale, die wir auch sonst bey weitem für die gelungensten Stücke halten, hat sich Hr. H. mehr frey gemacht von bestimmtem Nachbilden.

The beginning of the dark theme of the second part sounds like this in the first bars:

In this part too, the composer goes polyphonic. One of the forms of this theme is as follows:

The themes of the last part resemble the theme of the first part. After the first note there is always a leap. In the first theme that leap is a sixth:

In bar 25 the leap is again an octave (as in the first part) and a fugal episode of 16 bars follows:

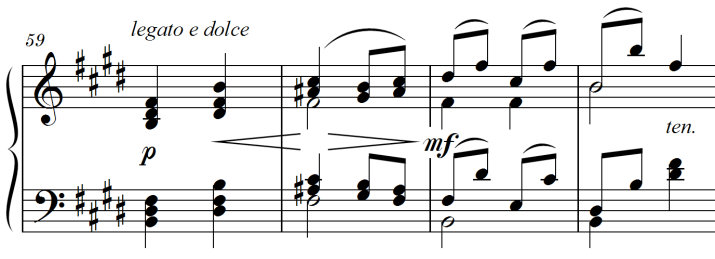

And in bar 59 the leap is a quarter and still recognizable as a related theme:

.

What makes this sonata so attractive and striking is the alternation of virtuoso, early-romantic passages with solid romantic polyphony. But there is also much to enjoy rhythmically, harmonically and melodically.

And there is another striking aspect to Hartknoch. The example below comes from opus 6, Grand rondeau russe (±1825). With the fingering (added by me) this passage is easy for the right hand:

Another example from the same rondeau:

These passages sound virtuoso without being technically difficult, which is remarkably early for 1824 or 1825. Hartknoch’s Violin Sonata opus 2 (±1823) also contains easy passages here and there. For example:

With Hartknoch’s teacher Hummel, such passages can be found in the Piano Concerto opus 113 from 1827. In earlier opus numbers, as far as I could find, I have not come across it. In the third piano sonata from 1816 (opus 49, third part) by contemporary Carl Maria von Weber, this is found (and that seems to be a very early example):

But it is Chopin who we associate most with this way of composing. His first opus appeared in 1825 (very probably also the year of Hartknoch’s Grand rondeau russe) and in it the composer shows in several places what he would later be able to do much more extensively. An example from this opus:

Apparently, it was in the air to write for piano in such a new way. It is pianistic that Chopin usually achieves by alternating black and white keys in combination with pedal. The aim is a harmonious interaction of the hands with the keyboard, with white keys being played by the thumb as much as possible.

But even if black keys are missing for a while, it can work. We already saw that in example 11. Some things are only possible with the right fingering. In opus 4 (1829), Chopin has the right hand quickly shoot over the white keys while smoothly bridging large distances:

Also in the rondeau of Hartknoch is an example in F major with many, but not only, white keys:

There is another passage in Chopin’s opus 1 that should not go unmentioned:

And Hartknoch writes in his sonata composed (about) 5 years earlier:

Although the two pieces breathe a slightly different atmosphere, the similarity seems more than coincidental. As Jan Marisse Huizing shows (in his book ‘De Chopin etudes in historisch perspectief’), Chopin almost never made clear what inspired him, while occasionally there are unambiguous similarities between his compositions and those of, for example, Hummel or Beethoven. It is up to the reader to determine whether or not the above passages are coincidentally similar.

Of course, Hartknoch is little more than a footnote in the piano literature and the comparison with Chopin can hardly be sustained. He died too young and started composing too late to write a significant oeuvre. Although he was appreciated for his piano playing, the reviewer who discusses his sonata also has a comment: Eben darum müssen wir aber…wünschen, dass er künftig für die Ausführung des Spielers zu schreiben sich bemühe. He advises the composer, who is still at the beginning of his career and should make an effort to interest the public, to write somewhat more simply and easily. It seems that this advice was not followed. The pieces I have in my possession are certainly not easy, except perhaps for the three Nocturnes opus 8. His voluptuous writing style, mixed with polyphony and virtuoso passages, has probably not contributed to his popularity. But remarkably enough, it is precisely these qualities that make him attractive to today’s pianist.

Hartknoch’s music has more than enough quality to justify a small rediscovery.

In the latest edition of Van Sambeek Edities (which will be published soon) three opus numbers are included. In addition to the sonata and rondo discussed, opus 8, Trois nocturnes caractéristiques (±1833) is also included. See www.vansambeekedities.nl